William Beanes, M.D. is a name that should be more well-known than it is, but we are working to correct that and give him the recognition that he deserves.

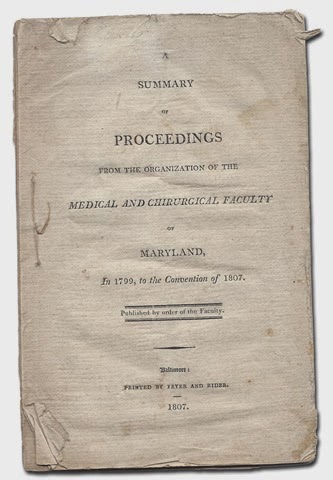

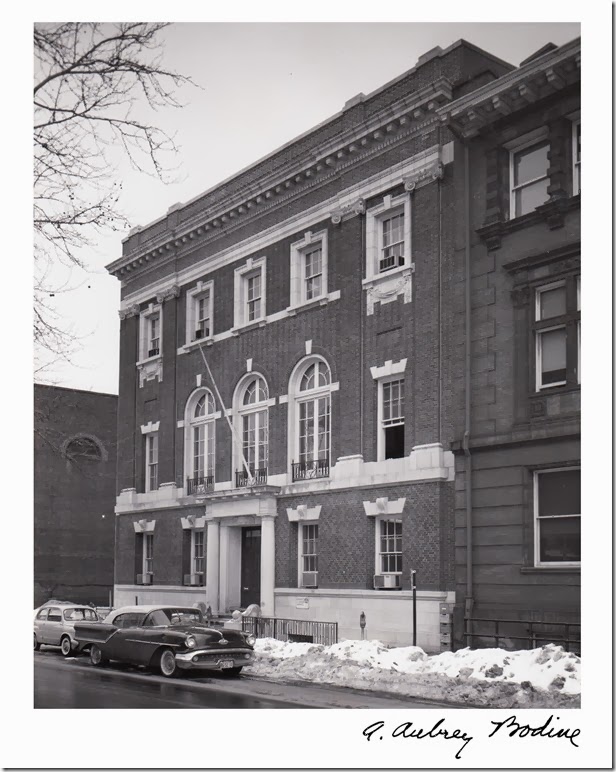

The Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland was founded in 1799, just years after our country was born. Many of MedChi’s early members had fought in the American Revolution, and were prepared to fight again in the War of 1812, and in the Battles of North Point and Baltimore, which took place in September of 1814.

Fort McHenry, which was defended during the Battle of Baltimore, was named after another of MedChi’s earliest members, James McHenry. However, it is one of our founding members, William Beanes, M.D. of Prince George’s County, Maryland, who played a pivotal, yet largely unknown, role in the history of our National Anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner.

If not for Dr. Beanes, Francis Scott Key would not have been on a ship in Baltimore’s Harbor, and he would never have written the poem which became our National Anthem.

Here is the story of William Beanes, M.D.

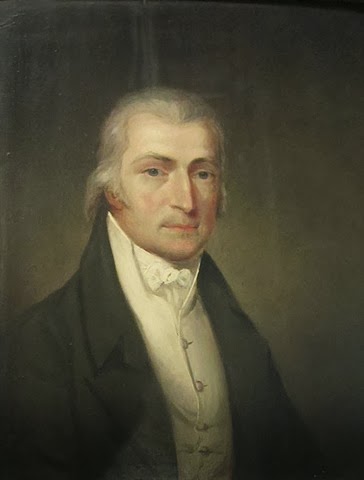

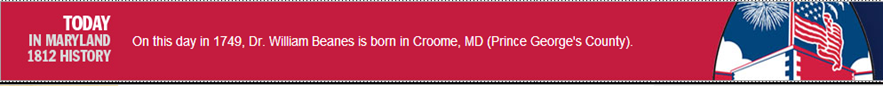

William Beanes was born at Brooke Ridge, a thousand-acre farm near Croome in Prince George's County, on January 24th, 1749.

William Beanes was born at Brooke Ridge, a thousand-acre farm near Croome in Prince George's County, on January 24th, 1749.

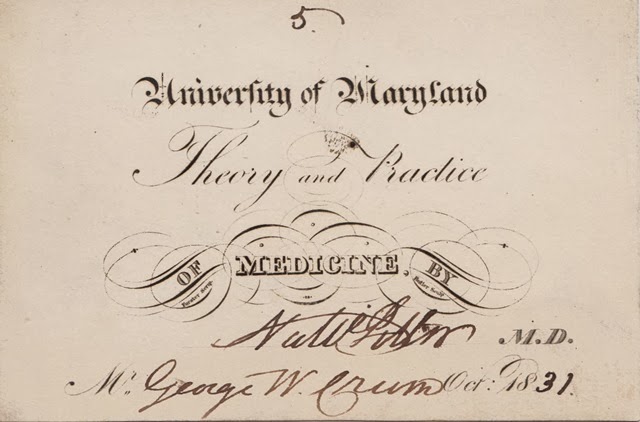

There were no medical schools when Dr. Beanes studied medicine, so he most likely apprenticed with a local physician. Professionally, his reputation spread beyond the county, and in 1799, when the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland was established, he was one of its founders and a member of its first examining board.

As the War of 1812 raged, in August of 1814, the British Army sailed up the Potomac River, planning to burn the young nation’s capital, Washington, to the ground. Some of the army marched up the banks of the Patuxent and Potomac Rivers, and through Upper Marlborough, where Dr. Beanes lived.

British General Ross selected Dr. Beanes’ home as his headquarters, and Dr. Beanes agreed not to object to his presence or cause the troops harm. Because Beanes chose not to fight against the occupation of his home, he was believed to be sympathetic to the British cause. Unbeknownst to the British, however, because it was feared that the British would burn the capital city of Annapolis, Dr. Beanes had secretly hidden Maryland state records on his property for safekeeping.

However, when the British Army returned to Upper Marlborough after burning Washington, they were jubilant, drunk and marauding. Dr. Beanes and some of his neighbors were forced to arrest some of the most badly behaved of the group. One prisoner escaped and reported to General Ross that Dr. Beanes had taken some prisoners.

General Ross returned to Upper Marlborough and arrested Dr. Beanes in the middle of the night. There was great outrage at Dr. Beanes’ arrest, and for the “great rudeness and indignity heaped upon a respectable and aged old man.” Dr. Beanes travelled with the British Army down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay, as the British prepared to burn Baltimore, “a nest of pirates”, as they had done to Washington.

At the same time, a young lawyer named Francis Scott Key, a nephew of MedChi’s first President, Upton Scott, was engaged to free Dr. Beanes from the British Army. Key travelled to Baltimore with letters of support from President James Madison, as well as letters from British prisoners whose injuries Dr. Beanes had treated only weeks earlier in Upper Marlborough.

Dr. Beanes was being held on the Minden, a truce ship in the waters just south of Baltimore, and Key sailed out to the Minden to negotiate for his release. While Key was negotiating with the British, the Battle of Baltimore was beginning. For more than 25 hours the battle raged, and bombs rained down on Fort McHenry from the British ships moored in the Patapsco River. Dr. Beanes and Francis Scott Key watched and waited all through the night. As long as bombs were being shot back from the Fort, the men knew that all was not lost and the Fort still stood. Towards the morning, the cannon fire slowed and then stopped, followed by an ominous silence from across the water. Both men were gripped by hope and fear. Was the Fort lost to the British and would Baltimore suffer as Washington had, just weeks earlier?

Dr. Beanes and Francis Scott Key watched and waited all through the night. As long as bombs were being shot back from the Fort, the men knew that all was not lost and the Fort still stood. Towards the morning, the cannon fire slowed and then stopped, followed by an ominous silence from across the water. Both men were gripped by hope and fear. Was the Fort lost to the British and would Baltimore suffer as Washington had, just weeks earlier?

As the dawn broke, Francis Scott Key and Dr. Beanes were able to see that the flag was still there, flying above Fort McHenry. They knew that the British had not been able to capture Baltimore.  As the men sailed back to Baltimore, Francis Scott Key penned the now famous poem on the back of an envelope. It was printed in a local paper and then set to the tune of an old drinking song, To Anacreon In Heaven.

As the men sailed back to Baltimore, Francis Scott Key penned the now famous poem on the back of an envelope. It was printed in a local paper and then set to the tune of an old drinking song, To Anacreon In Heaven.  Dr. Beanes returned to his home, Academy Hill in Upper Marlborough, and continued to practice medicine. He died at age 80 in October of 1828. Dr. Beanes is buried in a small graveyard in Upper Marlborough, and is remembered throughout Prince George’s county where several roads, schools and parks bear his name, and continue to tell his story.

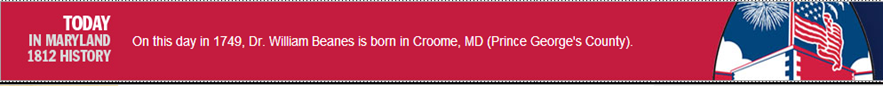

Dr. Beanes returned to his home, Academy Hill in Upper Marlborough, and continued to practice medicine. He died at age 80 in October of 1828. Dr. Beanes is buried in a small graveyard in Upper Marlborough, and is remembered throughout Prince George’s county where several roads, schools and parks bear his name, and continue to tell his story.

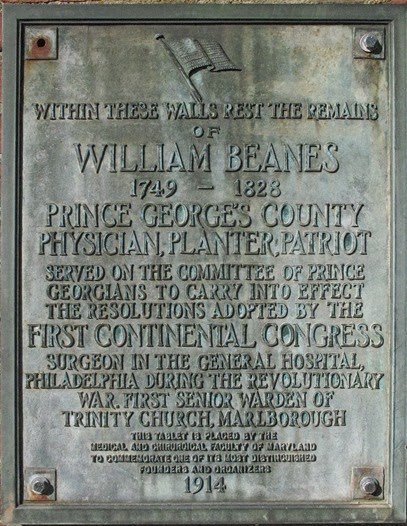

In 1914, MedChi placed a bronze plaque at the gates to the graveyard.  In October 2013, MedChi President, Russell Wright, MD, participated in a ceremony at the gravesite where the Daughters of the War of 1812 placed a new plaque detailing Dr. Beanes’ role in the Star-Spangled Banner.

In October 2013, MedChi President, Russell Wright, MD, participated in a ceremony at the gravesite where the Daughters of the War of 1812 placed a new plaque detailing Dr. Beanes’ role in the Star-Spangled Banner.

During the coming year, which is the 200th Anniversary of the writing of the National Anthem, MedChi will be hosting events to celebrate our role in both that and the Battles of Baltimore, North Point and Bladensburg.

William Beanes was born at Brooke Ridge, a thousand-acre farm near Croome in Prince George's County, on January 24th, 1749.

William Beanes was born at Brooke Ridge, a thousand-acre farm near Croome in Prince George's County, on January 24th, 1749.