Last week, we hosted a reporter, photographer, and videographer from the Baltimore Banner, a non-profit digital newspaper here in Baltimore. They were interested in meeting Marcia, and published this wonderful piece about her.

The ghost of Marcia Crocker Noyes, the librarian of 50 years at the Maryland State Medical Society's library in Mount Vernon, is often heard and sometimes seen in the library stacks, the reading room and her old office. These images were created in-camera with the double-exposure method using a portrait of Noyes over the places she’s haunted.

She May Be Baltimore's Least Famous Ghost. Want to Meet Her?

By Meredith Cohn. Photography by Kaitlin Newman

For a half century, Marcia Crocker Noyes built and oversaw a collection of 60,000 books that offered guidance of the day to the region's doctors.

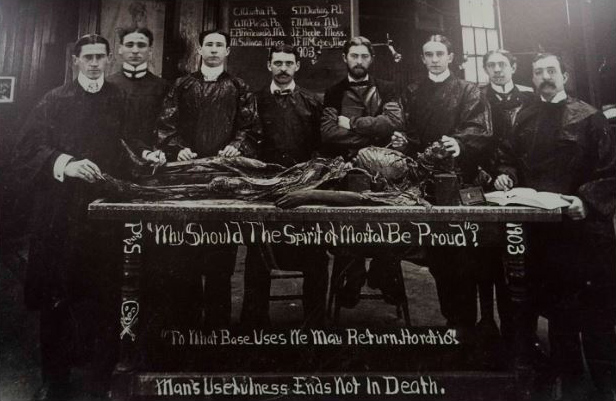

The journals on the library shelves at the Maryland State Medical Society would helpfully call for a dose of heroin to calm the anxious and beer to ensure youngsters got enough vitamins. For an "epilectic fit," it was "boxing," or hitting the ears.

"That would clearly not work," said Meg Fairfax Fielding, head of the History of Maryland Medicine program for the society, caretaker of the (mostly very outdated) books.

Meg Fairfax Fielding, head of the History of Maryland Medicine for the Maryland State Medical Society, pictured on Aug. 2, 2023.

"But Marcia was hired in 1896 and as part of the job was required to live and work on the premises so she was available at all hours when the doctors called," she said. "If they called in the middle of the night and said my patient's eyeball fell out, she'd get a book on eyeballs for them."

The ghost of Marcia Crocker Noyes, the librarian of 50 years at the Maryland State Medical Society’s library in Mount Vernon, is often heard, and sometimes in the library stacks. These images were created in-camera with the double-exposure method using a portrait of Noyes over the locations she’s haunted.

Legend has it that Marcia, as she's still regularly and fondly called, was so dedicated to her position as the medical librarian that she never left - even after she died in 1946.

Marcia is now the society's resident ghost and "more friendly than spooky," said Fielding, though she acknowledges occasional goosebumps. She's sure she's heard Marcia walking and pushing her wood cart of books. She's also found objects moved from where she was sure she left them the day before. Others in the Mount Vernon buildings swear they have seen Marcia.

Nondoctors and outsiders to the society known as MedChi, which now represents thousands of doctors in the state, soon may get the chance to meet the erstwhile librarian. Next year on the 225th anniversary of the society's founding as the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of the State of Maryland, officials plan to open a medical history museum. (Chirurgical is the old-timey word for surgery.)

It's not that the city needs more macabre bona fides. (See: birth of the Ouija board, death of Edgar Allan Poe and myriand haunted Fells Point pubs.) But Fielding and others would like to give Marcia some of the spotlight, even if most people will never see her.

Marcia was pretty well known in her circles in her day, a circle that was ever growing with the rise of two medical behemoths on opposite sides of Baltimore: the University of Maryland and the Johns Hopkins University schools of medicine.

She was more or less married to the job, living in a small apartment above her dusty four-story stacks of books encompassing the upper floors of the MedChi headquarters on Cathedral Street.

The ghost of Marcia Crocker Noyes, the librarian of 50 years at the Maryland State Medical Society’s library in Mount Vernon, is often heard or seen in the library stacks.

The library stacks at the Maryland State Medical Society are extensive, going up several floors.

She was recruited from the city's Pratt library system to the role of medical librarian at age 27 despite having no medical training by Dr. William Osler, early contributor to medical education and the library. Its initial purpose was to reduce "quackery" among medical providers, Fielding said, never mind that ear boxing thing.

Many books in the Maryland State Medical Society library date to the 18th century. (Left) Historical medical artifacts and tools are on display behind glass at the Maryland State Medical Society on Aug. 2, 2023. (Right)

Marcia grew the collection from a few thousand books to tens of thousands. She also helped establish the Medical Library Association that named an award in her honor. Doctors came to respect her. Osler was known to bring her bouquets of flowers.

The library stacks at the Maryland State Medical Society are extensive, rising up several floors.

Despite her relative anonymity compared to the more high-profile dead Baltimoreans, Marcia has her admirers. She and the library made it onto this year's Top 5 List of Haunted Spots compiled by Baltimore Ghost Tours.

Melissa Rowell, a tour co-founder, included the library on the list after interviewing MedChi staff years ago. The building is not actually on the the tour, as it's a bit too far north from the Fells Point ghostly epicenter and currently not open to the public.

But, Rowell said, "I never forgot the story. The most striking thing is that so many people over the years had seen or heard her."

Marcia Crocker Noyes, MedChi’s librarian of 50 years, has been known to haunt the reading room.

To be fair, the building feels plenty haunted without the ghost. There are century-old portraits of gray-haired doctors with clasped hands who never take their eyes off you no matter where you move, cabinets of bone saws and assorted other "medical" devices and vials of poisons.

Photographs and historical documents are on display at the Maryland State Medical Society on Aug. 2, 2023

And yeah, there is a ghost milling about. One of those sightings was made in the early morning hours. A housekeeper was in a meeting room and saw a woman standing on the dias. She looked away for a moment and the woman was gone.

Concerned about a stranger in the building before the normal work day, she told Russ Kujan, an employee on hand.

"Who else could it be?" Kujan said with a grin.

He showed the housekeeper a picture of the librarian, dressed in her mid-century garb and shining her piercing blue eyes. The housekeeper insisted it was the same woman. Afterward, the story goes, she wouldn't agree to be in the building alone and soon resigned.

But Fielding insists Marcia is more of a jokester than a creeper. She drops things at just the right momemt to register her presence. She flickers lights to file her support or objection during a conversation. She moves picture frames in the night, just because.

Medicine may be a serious business. But thise medical librarians, always a hoot.

Originally published by the Baltimore Banner

August 8, 2023

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)