Today marks the 391st anniversary of the founding of the state of Maryland. The Medical & Chirurgical Faculty is proud to have been a part of Maryland for 225 of those years.

If you're interested in learning about the founding of MedChi in 1799, please click here. As long as there is a State of Maryland, there will be a Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland.Tuesday, March 25, 2025

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Women in Medicine - A Brief History

As you may know, we hosted a Women's History Month Symposium on March 1. I am going to share each of the speakers' talks, starting with mine.

In 1886,

MedChi welcomed its first woman member, Dr. Amanda Taylor Norris. In addition

to being the first woman member, Dr. Norris was the first woman with a medical

degree to practice in Baltimore.

She

graduated in 1880 from the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania and returned

to Baltimore where she began her career. The Baltimore Medical College, a small

school, offered her a faculty position as a demonstrator of anatomy, which she

readily accepted.

As with

most physicians of the day, Dr. Norris was a generalist. She taught materia

medica, or the pharmaceutical aspects of medicine, practical obstetrics and

gynecology, and throat and chest medicine. Dr. Norris was also the physician to several

women’s clinics including the Female House of Refuge and the Evening Dispensary

for Women and Girls, which I will talk about shortly.

Before 1911, there were eleven medical schools in Baltimore.

That changed when the Flexner Report was published. This compared all medical

schools in the US to Johns Hopkins, a new and well-funded medical school. Most

other med schools were small and ill-funded and paled in comparison.

Originally

located on Eutaw Street, the college moved several times in its nearly 30-year

lifetime. It

was one of the earliest schools to require either a college diploma or an

entrance exam to attend. Because of the scarcity of women’s medical schools, women from around the world

attended the college.

The

Women’s Medical College closed in 1910, mainly due to lack of an endowment to

keep it going. In the Flexner report, it was stated that the laboratories were

scrupulously well-kept and showed a desire to do the best possible with meager

resources. It also mentions the Women’s Dispensary at the College. The College

would probably have closed regardless, due to paring down of medical schools

after the Flexner report.

From the beginning, women were admitted to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The men at Hopkins hated the fact that women were students, but since philanthropist,

The University of Maryland’s School of Medicine did not admit women until 1919, just before women received the right to vote. There had been a shortage of physicians for a few years due to World War One, and so it was more of a necessity that women were admitted to medical schools.

The Dispensary also provided an opportunity for female medical students to gain practical experience. In addition to providing free care for poor women, it also provided a clean milk distribution system for sick babies, social services, a visiting nurse program, and public baths.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, there were a number of hospitals for women and children.

The ones for women in the late stages of pregnancy were called “lying-in” hospitals. The Maryland Nursery & Child’s Hospital was also for foundlings.There one additional woman I’d like to briefly talk about: Marcia Crocker Noyes.

She was not a physician, but the librarian at MedChi for 50 years. She was recruited by Dr. William Osler, one of the “Big Four” at Hopkins in 1896.

In 1904, Marcia became the Executive Secretary of the “Faculty” and oversaw all of the numerous activities in the buildings and for the members. She was highly respected by the physicians of the day. She owned her own car in the mid 19-teens, and was a member of the suffrage movement, which you just learned about. She traveled extensively in the US and abroad. She owned a “Camp” in the Adirondacks and would sail to England to visit her friend, now-Sir William Osler.

In 1946, Marcia became ill, so the physicians advanced her 50th anniversary party by a few months.

She died just a few days after her 50th anniversary in November of 1946 and is buried at Greenmount Cemetery. She remains here in the building as our friend and sometime companion.Thank you so much.

Wednesday, January 15, 2025

Women's Symposium to Celebrate Women's History Month

A few months ago, I was thinking about our history (actually, I think about MedChi's history all of the time!), and thought about the early women members, women in medicine today and more.

As I thought about how we could commemorate women, I realized that Women's History Month is in March. Things came together and we decided to host a Women's Symposium.

The event will take place on Saturday, March 1, from 9:30 to 12:30 at MedChi HQ at 1211 Cathedral Street, or 1204 Maryland Avenue (front and back doors). We will begin at 9:30 with a coffee meet-and-greet session and the welcome and first lecture will begin at 10:00.

We have on-site parking, and there is on-street parking and public transportation in the immediate vicinity.

Tickets are $10 per person and will benefit the preservation of MedChi's archives. For more information, or to secure a reservation, please click or scan the QR code below.

We will look forward to seeing you then!

Friday, September 20, 2024

The 2024 Hunt History of Medicine Lecture

One of the highlights of the History Committee's work is the annual Thomas E. Hunt, Jr., MD History of Medicine Lecture. And there was only one topic that we could present this year - Our Own History!

MedChi President, and medical history aficionado, Benjamin H. Lowentritt, MD, FACS, will present this year's lecture on the history of MedChi, "From Leeches to Lasers: 225 Years of Service."

This year's lecture will take place on Tuesday, October 22 from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. The evening will begin with a light reception and the lecture will begin at 6:00 p.m. There will be a time for questions and answers after the lecture.

Again this year, we will be presenting the lecture in hybrid form, but hope that you will join us in person and take the opportunity to visit the MedChi Museum of Maryland Medical History.

When you RSVP, please let us know whether you will be attending in person or via Zoom. Additional details, including parking, will be sent out shortly before the event. If you have any questions, please email Meg Fielding HERE.

We will look forward to seeing at the Hunt Lecture!

Thursday, August 29, 2024

Some Personal News

After working on the History of Medicine in Maryland part time for the past ten years (I was Director of Development for the rest of the time), I will be doing History full time for the foreseeable future.

Among the tasks I have set for myself are:

- Maintain, manage, and expand the Museum, including the Rare Book Room

- Source specific items relevant to MedChi and the Museum

- Seek funding sources specific to the Museum’s needs

- Establish a Museum Advisory Committee to meet twice a year, and on ad hoc basis

- Plan new exhibits

- Conduct scheduled and un-scheduled tours

- Curate MedChi’s art and ephemera collections

- Create additional videos for the Museum (original plan - 12 videos/eight finished)

- Source in-kind donations for the Museum

- Research and write regular posts for the MedChi Archives Blog, and maintain the site

- Provide information to the social media staff for history of medicine items.

- Submit history articles for Maryland Medicine magazine

- Research, write and publish biography of Marcia Crocker Noyes

- Continue the association with American Osler Society via membership and conferences.

- Staff the History of Medicine Committee

- Meet with scholars and researchers who want access to our non-digitized items

- Respond to member and non-member requests for historical information

- Be a resource for outside historians.

- Adhere to the American Association of Museums’ gift acceptance guidelines

- Finish digitizing the 1930-1950 Medical Bulletins and post on-line

- Apply to the National Archives for a grant to preserve the archives, including climate control and security of the Krause and Rare Book Rooms

- Schedule Ghost Tours for outside groups, including the Halloween Tours, the BSO (we have donated a Ghost Tour to their 2024 Silent Auction) and others

- Create a resource file and master index to item locations.

Monday, May 13, 2024

We're Going to Party, Like it's Our Birthday!

Sigh, we're 115 years old today, and sometimes we feel every year of that.

Saturday, January 20, 2024

Today's the Day! We are 225 Years Old!

“In all ages of the world, men engaged in the same pursuits

have united together for purposes of mutual advantage or protection.” So begins

Eugene Fauntleroy Cordell’s masterwork, “The Medical Annals of

Maryland, 1799 to 1899.”

Prior to the American Revolution, all but one of the Thirteen Colonies had a medical society. Although Maryland was one of the oldest colonies, it was the seventh state to establish a medical society.

In 1779, Dr. Charles Wiesenthal made the first

attempt at establishing a state-wide society of physicians, but the idea did

not catch on. In 1790, Dr. George Buchanan wrote a letter to the citizens of

Baltimore, and suggested the registration of deaths and the organization of a

humane society. Again, the idea did not catch the attention of the city’s

physicians.

However, many “physicians” objected to this proposal and the

original petitioners concluded that they were surrounded by “swarms of quacks.”

The petition was presented to the legislature, but it did not pass. At the

time, there were no formal medical schools in Baltimore, so Drs. Buchanan and

Wiesenthal began to lecture on the topics of anatomy, physiology, pathology,

and operative surgery.

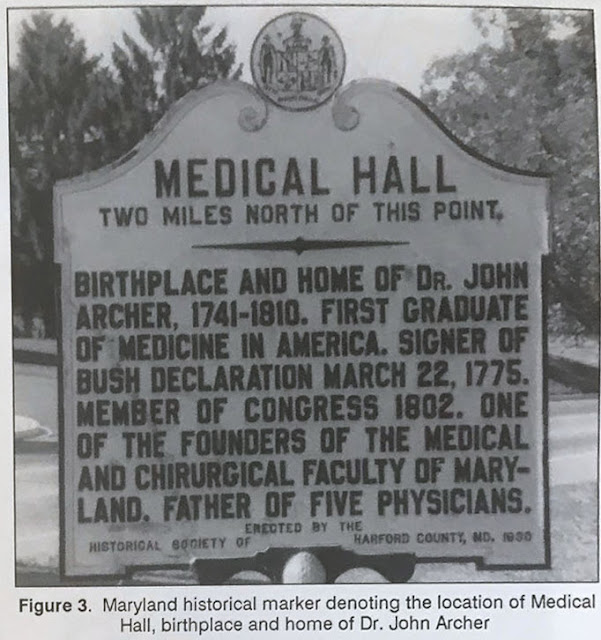

In Harford County, a group including Dr. John Archer,

his sons and the students at Dr. Archer’s Medical Hall,The first attempt at organizing left an impression in the minds of physicians for more than a decade and in 1798, the organizing began again. Several physicians were recruited from each of the then-19 counties of Maryland, and from the

towns of Annapolis and Baltimore, and eventually they became the 101 founders. These men had trained at the best medical schools of the time – in Paris, Oxford, Edinburgh, and Dublin in Europe, and locally, in Philadelphia.In January of 1799, an act to establish and incorporate the Medical & Chirurgical Faculty in the State of Maryland finally secured the majority vote of the legislature.

The act directed physicians to promote and disseminate medical and chirurgical knowledge and prevent citizens from risking their lives at the hands of ignorant practitioners and pretenders to the medical arts.The first officers were to be

a President, Secretary, and Treasurer, as well as a 12-member Board of

Examiners “of the greatest chirurgical abilities in the State.” Seven of the

members would come from the Western Shore and five from the Eastern Shore.

Each person who was examined and received a medical license would pay the sum

of $10.00. Members elected to the Society would pay the same fee.

A name was given to the organization, and was declared to be “one community, corporation and body politic, known forever by and under the name of The Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of the State of Maryland.

The annual meetings were set for the first Monday in June, beginning in 1799 and then on the same date every other year afterward.However, nothing documents the first gathering of the group,

and it’s left up to Dr. Cordell’s imagination. He mentions that he has a

medical diary and notebook from Professor Nathaniel Potter from

1799, but the establishment of the organization is never discussed.

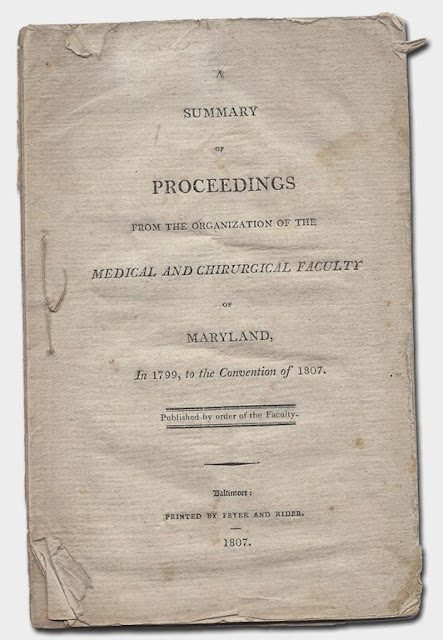

Additionally, for the first half century of the Faculty’s existance, there are very few records, save the brief “Summary of Proceedings” published in 1807.

The yearly Transactions weren’t published regularly until 1853.However, members published occasional papers and presented orations over the years and some of them remain in their original hand-written form.

Additionally, notices and advertisements were placed in local newspapers and medical journals, especially in Baltimore, document our earliest days.Tuesday, September 12, 2023

Dr. Beanes and the Star-Spangled Banner

Most people don't know that September 13-14 is a special time in American History: This is when the British bombed Baltimore for 25 hours. The city stood, and so did the nation. It was also when our country’s National Anthem was written.

Most people also don't know that one of the Medical & Chirurgical Faculty’s founding members had an essential role in it. William Beanes, M.D. is a name that should be more well-known than it is, but we are working to correct that and give him the recognition that he deserves.

Here is the story.

The Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland was founded in 1799, just years after our country was born. Many of MedChi’s early members had fought in the American Revolution, and were prepared to fight again in the War of 1812, and in the Battles of North Point and Baltimore, which took place in September of 1814.

Fort McHenry, which was defended during the Battle of Baltimore, was named after another of MedChi’s earliest members, James McHenry. However, it is one of our founding members, William Beanes, M.D. of Prince George’s County, Maryland, who played a pivotal, yet largely unknown, role in the history of our National Anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner.

If not for Dr. Beanes, Francis Scott Key would not have been on a ship in Baltimore’s Harbor, and he would never have written the poem which became our National Anthem.

William Beanes was born at Brooke Ridge, a thousand-acre farm near Croome in Prince George's County, on January 24, 1749.

There were no medical schools when Dr. Beanes studied medicine, so he most likely apprenticed with a local physician. Professionally, his reputation spread beyond the county, and in 1799, when the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland was established, he was one of its founders and a member of its first examining board.

As the War of 1812 raged, in August of 1814, the British Army sailed up the Potomac River, planning to burn the young nation’s capital, Washington, to the ground.

Some of the army marched up the banks of the Patuxent and Potomac Rivers, and through Upper Marlborough, where Dr. Beanes lived.British General Robert Ross selected Dr. Beanes’ home as his headquarters, and Dr. Beanes agreed not to object to his presence or cause the troops harm.

Because Beanes chose not to fight against the occupation of his home, he was believed to be sympathetic to the British cause. Unbeknownst to the British, however, because it was feared that the British would burn the capital city of Annapolis, Dr. Beanes had secretly hidden Maryland state records on his property for safekeeping.However, when the British Army returned to Upper Marlborough after burning Washington, they were jubilant, drunk and marauding.

Dr. Beanes and some of his neighbors were forced to arrest some of the most badly behaved of the group. One prisoner escaped and reported to General Ross that Dr. Beanes had taken some prisoners.General Ross returned to Upper Marlborough and arrested Dr. Beanes in the middle of the night. There was great outrage at Dr. Beanes’ arrest, and for the “great rudeness and indignity heaped upon a respectable and aged old man.” Dr. Beanes travelled with the British Army down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay, as the British prepared to burn Baltimore, “a nest of pirates”, as they had done to Washington.

At the same time, a young lawyer named Francis Scott Key, a nephew of MedChi’s first President, Upton Scott, was engaged to free Dr. Beanes from the British Army.

Key travelled to Baltimore with letters of support from President James Madison, as well as letters from British prisoners whose injuries Dr. Beanes had treated only weeks earlier in Upper Marlborough.Dr. Beanes was being held on the Tonnant, a truce ship in the waters just south of Baltimore, and Key sailed out to negotiate for his release. While Key was negotiating with the British, the Battle of Baltimore was beginning.

However, before the sea battle even started, General Ross was killed by an American sharpshooter as he led his troops over land to Baltimore.

For more than 25 hours the battle raged, and bombs rained down on Fort McHenry from the British ships moored in the Patapsco River.

Dr. Beanes and Francis Scott Key watched and waited all through the night. As long as bombs were being shot back from the Fort, the men knew that all was not lost and the Fort still stood. Towards the morning, the cannon fire slowed and then stopped, followed by an ominous silence from across the water. Both men were gripped by hope and fear. Was the Fort lost to the British and would Baltimore suffer as Washington had, just weeks earlier?

As the dawn broke, Francis Scott Key and Dr. Beanes were able to see that the flag was still there, flying above Fort McHenry. They knew that the British had not been able to capture Baltimore.

As the men sailed back to Baltimore, Francis Scott Key penned the now famous poem on the back of an envelope. It was printed in a local paper and then set to the tune of an old drinking song, To Anacreon In Heaven.

Dr. Beanes returned to his home, Academy Hill in Upper Marlborough, and continued to practice medicine. He died at age 80 in October of 1828. Dr. Beanes is buried in a small graveyard in Upper Marlborough,

and is remembered throughout Prince George’s county where several roads, schools and parks bear his name, and continue to tell his story.In 1914, MedChi placed a bronze plaque at the gates to the graveyard.

In October 2013, MedChi President, Russell Wright, MD, participated in a ceremony at the gravesite where the Daughters of the War of 1812 placed a new plaque detailing Dr. Beanes’ role in the Star-Spangled Banner.