Baltimore's Historic Hospitals

The entire lecture is on YouTube here. This virtual lecture was given in conjunction with the Baltimore Architecture Foundation.

While we tend to think

there are about six hospitals in Baltimore, there were at least sixty that I

counted, the earliest dating from the 1700’s. And while hospitals these days are

mostly generalists, hospitals during the 1800’s dealt with incredibly specific

disorders, as we will see.

Due to time constraints, I

had to whittle down my list to about 20, which we will visit in chronological order.

I have bundled several similar hospitals together: for example, there were at

least five eye, ear and throat hospitals, and a similar number of maternity

hospitals.

One brief

note, I will talk a lot about dispensaries, which were mainly out-patient

clinics for the sick poor. A wide range of groups, including pregnant women,

children, incurables and those with contagious diseases were often excluded

from inpatient hospital services, so this was the reason for the dispensary

movement. There were 34 dispensaries in the city, including the First and

Second, the North, West, East & South Dispensaries, and ones for Nervous

Diseases, Ears, Noses & Throats, Women and Children, Hebrews and

Protestants, and even a homeopathic dispensary.

I have illustrated this

lecture with both historic and contemporary photographs, engravings, and

paintings from MedChi’s collection of historic portraits.

At the end, I will share

my sources with you. If you have questions, please type them into the comments and I will answer them.

Founded in 1773, as the “Baltimore

County and Town Almshouse,” it was initially located half a mile west of

the then city line. However, the expansion of the city resulted in a number of

relocations.

In 1820, the Almshouse moved to the

Calverton Mansion and stayed until 1866, when it made its final move to the

present location. The name was changed to Bay View Asylum because of its close

proximity to the Chesapeake. In the mid-1880s, William H. Welch began

seeing patients there as part of his research, creating the first connection

between the asylum and Johns Hopkins.

The transition to a hospital began in

1925 when Bayview became an acute and chronic care hospital and was renamed

Baltimore City Hospitals. In 1984, the City of Baltimore transferred ownership

of the Baltimore City Hospitals to Johns Hopkins Hospital, which renamed

it the “Francis Scott Key Medical Center.” In 1994, the name changed to the

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, to convey its strong connection

with Johns Hopkins.

William Hazlett Clendenin and Samuel Stringer Coale were both associated with the Almshouse during its earliest years.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

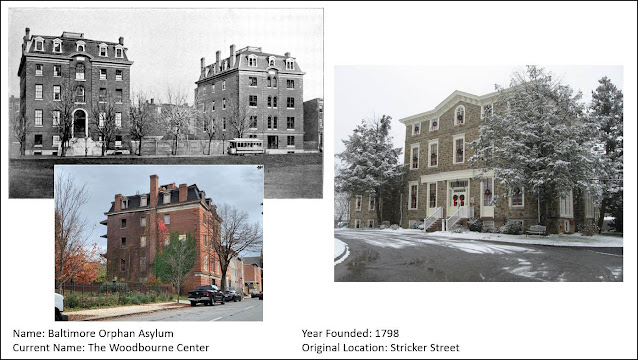

The Female Humane

Associated Charity School was founded when a group of women banded together to

assist widows and their children suffering in the aftermath of the

Revolutionary War. Over the years, it merged with other organizations,

including the Female Orphaline Charity School, Baltimore Female Orphan Asylum, the

Home of the Friendless and finally the Baltimore Orphan Asylum. It moved around

the city from Calvert to Mulberry to Stricker Street and finally, to Druid Hill

Avenue.

Children were given an

elementary education and girls were taught cooking, sewing, laundry and

housework, so as to find suitable positions as servants. Boys were taught a

trade.

In 1926, the Abell family

donated their property on Woodbourne Avenue, known as Marble Hall. The house,

known as Tivoli, had been the summer home of Enoch Pratt. In 1965, the name of

the organization was changed to Woodbourne, which remains to this day.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Medical &

Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland was founded in 1799 to prevent “quackery and

pretenders to the medical arts.” One hundred founders, four from each county in

Maryland, petitioned the legislature to establish an organization which would

set standards for medical practitioners in Maryland.

The name derives from

medicine, which is the scientific aspect of the profession, and chirurgury,

which is the old Latin word for surgery. The faculty aspect comes in 1807, when

members established what is now the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

For the next 180 years, the organization was known as the Faculty. It is now

known as MedChi, The Maryland State Medical Society, and is the professional

association for physicians in Maryland.

Upton Scott was the first

President of the Faculty. John Archer was the first person to receive a medical

diploma in the United States. John Crawford developed the first vaccines in

America. Marcia Noyes was the librarian who lived and worked at the Faculty for

50 years… and she’s still here. But that’s another entire lecture!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Baltimore

has been a port for all of its existance, and from the beginning, one thing

that the city wanted to do was prevent diseases from ships infecting the

citizens. Check points were established at Hawkins Point, close to where the

Key Bridge is, and Lazaretto Point, across from Fort McHenry, so ships could

stop and their crews could be given health checks. Anyone who was deemed unhealthy

was sent to the “Quarantine & Pest Hospital of the Port of Baltimore.”

The

Marine Hospital was for sailors on American-registered ships who became sick or

were injured in the line of duty. They initially applied at the Custom House

downtown, and were then moved to the hospital at Wyman Park. Dr.

Francis Donaldson was the only physician at the Marine Hospital who escaped an

epidemic of typhus which swept the hospital in 1848. The Marine Hospital later became a US Public Health Hospital, and now is

part of the Hopkins University Campus.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Over the years, there were a number of

dispensaries in Baltimore, but the Baltimore General Dispensary was first to open.

Dispensaries provided medical and health services to the poor in Baltimore. This

one was founded by Dr. James Crawford, who was also the founder and most active

member of the Maryland Society for Promoting Useful Information (something

which I’d love to join!). Many other members of the Faculty were associated

with the Baltimore General Dispensary over the decades, including Dr. Ashton Alexander, whose family gave their name to Alexandria, Virginia.

Funds to

support this Dispensary came from the state lottery, concerts, and “Fines

imposed on persons keeping houses of ill-fame.”

In 1959, a decision was

made to sell the Dispensary building and establish a foundation which would

grant money to the city’s hospitals for the free distribution of medicine at

out-patient clinics.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In 1807, the Legislature

passed a bill creating the College of Medicine in Maryland. However, this would

never have happened without the work of members of the Faculty, including Dr. John

B. Davidge. From the Annals of Medicine, published on our centenary: The

founding of this college, the forerunner of the University of Maryland,

emanated from and owes its existence directly to the Medical & Chirurgical

Faculty.

However, it was almost

over even before it started! Dr. Davidge owned a building on Liberty Street

where he began instructing students. He “procured a subject” and began anatomy

classes. Prejudice against dissection was great and the public was bent on

destroying the building and its contents. However, physicians had the opposite

reaction. They rallied to Davidge’s support, found another building, collected

funds and secured the necessary legislation to allow dissections to continue.

The story doesn’t end

there. What is now Davidge Hall was built in 1814, conveniently right around

the corner from the Westminster Burying Ground, and there are stories about the

medical staff procuring cadavers from the newly dug graves for the students to

dissect!

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Church Home &

Hospital was originally founded as the Washington Medical College in 1835. Dr.

Horatio Gates Jameson was the head, along with five other physicians.

Edgar Allan Poe was taken to

this location when he was found semiconscious and ill in a street gutter near

East Lombard Street. This is where he subsequently died in October of 1849. It

is suspected that he died of rabies.

Dr. Jameson was in a

feud with another member of the Faculty, Dr. Frederick E.B. Hintze. Jameson’s

colleagues were jealous of him, and Hintze published a pamphlet disparaging

Jameson’s surgical skills, so Jameson sued. He was awarded $50, but Hintze

assigned away all of his property so not to have to pay Jameson.

The building was purchased in 1857 by the

Episcopal Church and renamed Church Home & Infirmary. Patients

were required to present a certificate indicating that they were free from

mental diseases before they would be treated.

The hospital closed in the early

2000s and the buildings are now used by Hopkins.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Between 1819 and 1825, Dr.

Horace Hayden delivered a series of lectures on dentistry to medical students

at the University of Maryland. In 1839, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery was chartered by the

Maryland State Legislature as the first dental school in America, because of

the need for systematic formal education

for the dental profession.

Dr. Hayden was a renaissance man, founding the Maryland Academy

of Science, and serving as its President.

He was a geologist and botanist, and published the first general book on

geology in America. He also discovered a mineral which he named "Haydenite."

The present dental school evolved through a series of

consolidations, the final taking place in 1923, when BCDS and the Dental

Department of the University of Maryland were combined to create a distinct

college of the university under state supervision and control.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

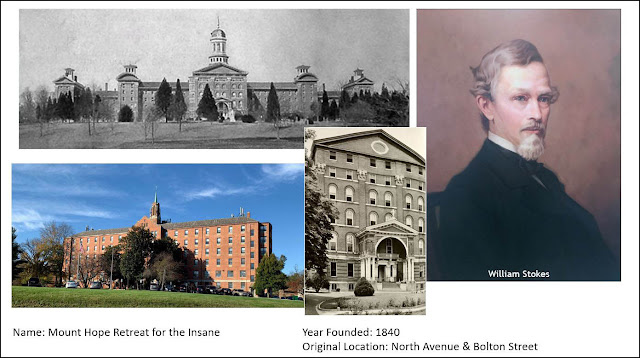

The Mount Hope Retreat was

a private, Catholic institution founded by the Sisters of Charity in 1840. In 1843, Dr. William H. Stokes became the

supervisor of Mount Hope Retreat, located just north of Baltimore City and held

the position for more than 40 years. Mount Hope was an atypical mental hospital

– it was open and bright, and used non-restraint methods of care, and a cottage

plan for residents.

There was an infamous trial against Dr. Stokes

and the Sisters of Charity alleging assault and false imprisonment of several

residents.

The lengthy trial came to an abrupt end when

the State said that it was “…unable to sustain the indictment under the

evidence offered. From beginning to end an utter shame and disgrace…” Dr.

Stokes, whom the State had sought to brand as a liar and conspirator, was a

gentleman whose life had been dedicated to the treatment of diseases of the

mind.

The current building, four stories, with a

two-story chapel, was built in 1911. In 1940, it was renamed the Seton

Institute. It closed in 1973 and the land was sold to the city for an office

park.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Moses Sheppard was a wealthy

Baltimore merchant and Quaker. By 1816, Sheppard amassed a substantial estate.

In addition to a store, he added a counting house, a twine manufacturing

company, and a tobacco warehouse.

Sheppard wanted to

improve conditions for individuals with mental illness, and envisioned an

institution that would feel more like a home than a prison, and treat patients

with respect and dignity. At his death in 1857, Sheppard left his fortune to

build the Sheppard Asylum, the largest bequest made to mental health at that

time.

Sheppard’s vision was

shared by Enoch Pratt, a local merchant and philanthropist. He admired

what was happening at The Sheppard Asylum, so on his death in 1896, he left it a

$2 million endowment, and the institution was renamed Sheppard-Pratt. Dr. Edward Brush was the superintendent of the hospital.

The original

buildings near Towson were designed by the architect Calvert Vaux. And if

anyone wants to see an intact MCM hospital setting, Sheppard Pratt’s Ellicott

City Campus is a prime example.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The College of Physicians and Surgeons was

incorporated in 1872 with 43 students. After a merger with Washington

University in 1878, CP&S moved to Calvert and Saratoga Streets, which was

connected to the Baltimore City Hospital. By 1880, the combined

school had an enrollment of 336 students from 23 states. All were men.

Both Dr. John Wesley Chambers and Dr. Isaac Ridgeway Trimble taught at the College.

The college had total medical control over Mercy

Hospital, Maternite Hospital, the Maryland Lying-in Asylum, the Hospital

for the Colored Race, the Dispensary, and the Pasteur Department for the Treatment

of Rabies. CP&S also used the Bay View Hospital and the Nursery and Child's

Hospital, so that students had numerous opportunities for clinical

experience. The hospital is the current Mercy Medical Center.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Southern/Maryland Homeopathic Medical College was chartered

in 1890 and was the first homeopathic

medical college south of the Mason-Dixon Line and east of the Mississippi. Homeopathy was founded by Samuel Hahnemann

based on the observation of the action of medicines on healthy persons, where

it could be seen unmodified by disease.

Southern Homeopathic College occupied a building

on Saratoga Street. In 1902, the school moved to a new building on Mount Street,

adjacent to the Maryland Homeopathic Hospital, providing clinical opportunities

for students.

The college closed in 1910, and the property was

sold to the Maryland Homeopathic Hospital, which was looking to

expand. However, by 1921 that facility had also closed.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum was organized in

1872 as a safe haven for Jewish immigrants and children. It was originally

funded by private contributions from prominent Hebrews in the city of

Baltimore. In 1874, it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1876 at a cost of

$50,000. It had a capacity of 150 inmates.

The younger children were taught at the

Asylum, and the older children went to local public schools. The boys were

taught a trade and the girls became seamstresses at local stores. Dr. Merville Carter was associated with the Hebrew Asylum for many years.

The orphanage moved to West Belvedere Avenue in

1923 once a better foster care system came

into practice. The building was reopened as the West Baltimore General Hospital

and later, Lutheran Hospital until the 1980’s when it closed once again.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum has recently

been completely renovated by our friends at Southway Builders.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Founded

in 1873 by Johns Hopkins with an endowment of $3 million, construction on the Johns Hopkins Hospital began in

1877, with buildings designed by Nielson and Niernsee. Originally

intended to be built at what is now Clifton Park, a better property closer to

downtown was purchased. The first patients were not admitted until 1888. The “Big

Four” William Osler, William Welch, William Halsted and Howard Kelly all helped

establish the hospital and the medical school, as well as its reputation as one

of the top hospitals in the world.

Hopkins

was one of the first medical schools to admit women, mainly because one of the

original donors, Mary Garrett required this before she would give them the

funding they needed.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

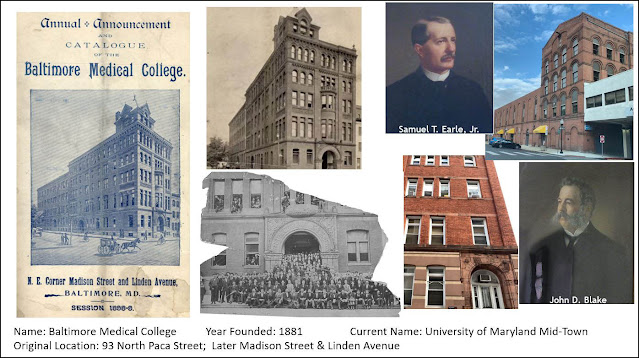

Baltimore Medical College

was founded by a group Baltimore physicians and advertised itself as a “practical

Christian medical school.” Among the twenty graduates in 1883 were four

women. The original offices of the college were in the YMCA building at 93

North Paca Street. In 1885, Maryland General Hospital was added to the college,

as was a dental department.

By 1888, BMC obtained a property on Howard Street,

just north of Madison. In 1895, they built a new five-story college building at

Howard Street and Linden Avenue. This contained a 600-seat lecture hall, a

500-seat amphitheater, a dispensary, and four laboratories. Drs. John Blake and Stephen Earle were both associated with the early years of the hospital and college.

In 1913, Baltimore Medical College merged with the

University of Maryland Medical College, but the ownership of Maryland General

Hospital was separate. One hundred years later, Maryland General became

UM-Midtown.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In 1881, the Sisters of Bon Secours sent three

members to Baltimore at the request of Cardinal Gibbons. Their convent was

located at West Baltimore and Payson Streets, where the hospital still stands.

By 1907, there were about 20 nuns at the mission,

nursing the sick, caring for children and performing other duties. In 1919,

they built a 20-bed hospital and in 1921, a nursing school. All Bon Secours

nuns become nurses, and “the order trained its own for many years.”

Dr. AlexiusMcGlannan was the President of Bon Secours Hospital and his wife was the first

woman medical school graduate from Johns Hopkins.

Over the years, the hospital has grown

continuously: in 1958, a new wing was built; in 1964, a new intensive-care

unit; in 1972, a new emergency room. It is now part of the LifeBridge group of

hospitals.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Presbyterian Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat

Charity Hospital was located at 1017 E. Baltimore St, where the building still stands.

It was founded by noted Civil War surgeon and former Dean of the University of Maryland

School of Medicine, Dr. Julian John Chisolm.

Baltimore

Charity E&E, E&E Dispensary of Church Home, E&E of Baltimore

General Dispensary, also, Baltimore Throat Dispensary all merged in 1882 to

become the Baltimore Eye, Ear & Throat Hospital

In 1961, Women’s Hospital sold

its building and equipment to the Baltimore Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital, and

acquired 42 acres from Sheppard-Pratt for the construction of GBMC. Through a series of moves and mergers, they ended up at GBMC, and recently,

the Presbyterian Eye, Ear & Throat Charity Hospital Board of Governors funded

their Cochlear Implant Center.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In an era

when women were not admitted to most medical schools, Baltimore had a medical

college for women. The Women’s Medical College was founded by two of the

Faculty’s members, Dr. Randolph Winslow and Dr. Thomas Ashby.

They wanted to provide a medical college for women

of the highest standard, so all applicants took a preliminary exam in order to

be admitted. There were on-site clinics and labs. Dr. Claribel Cone, one of the sisters responsible for the Cone Collection, the finest assemblage of modern French art in the United States, was a graduate of the Women's Medical College. Dr. Lillian Welsh was one of a group of women affiliated with the WMC and Goucher College.

The

Evening Dispensary for Working Women and Girls provided outpatient medical care

for women. It was especially important for two reasons: women could not leave

work in the daytime to go to a doctor’s appointment; and many women disliked

having male physicians. The Dispensary provided an opportunity for female

medical students to gain practical experience.

In

addition to providing free care for women, it also provided a clean milk

distribution system for sick babies, a visiting nurse program and public baths.

The women

who founded the Evening Dispensary were mainly graduates of the Women’s Medical

College. Contemporary accounts note that these early women physicians were

friends with the Suffragettes and proponents of women riding bicycles.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Whereas contemporary hospitals are generalists, in

the 1800’s, hospitals were quite specific. The Dispensary for Plaster of Paris

Jackets and Free Day School is one of those.

This dispensary specifically cared for women and

children suffering from curvature of the spine and scoliosis. Plaster of Paris

jackets were applied and then changed as the spine began to straighten. Miss

Charlotte C. Barnwell, a wealthy spinster, funded the clinic and applied the

plaster jackets herself.

Because of the unwieldly jackets, the children

could not attend regular school. The children lived at home, but came to the

clinic every day. The mornings were for white children and the afternoons were

for black children. Students were taught bible instruction, sewing, drawing, singing,

and physical exercises. Men were not admitted.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Until the latter half of the 19th century, most women gave birth at home, assisted by a mid-wife or a maid (think

Gone with the Wind), and physicians were rarely in attendance.

In May of 1887, the Free Lying-In Hospital of the University

of Maryland opened in Baltimore under the direction of Dr. George W.Miltenberger, who was President of the OB/GYN Society. (As an aside, the portrait in our collection of Dr. Miltenberger is my favorite.)

When this hospital opened, the only other

hospitals for women in Baltimore were the Maryland Woman's Hospital (shown here)

and the Maternité Lying-In-Asylum, both associated with the College

of Physicians and Surgeons. Part of the reason that medical schools opened

hospitals was so that their students would gain practical experience, and not

just academic instruction.

In addition to the private maternity hospitals,

the St. Vincent’s Infant Asylum also cared for “unfortunate women needing

reformatory influences.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Founded in 1895 by Dr. R. Tunstall Taylor, the Hospital for

Crippled and Deformed Children was originally located at 6 West 20th Street. It was a free orthopaedic hospital for “crippled and deformed children.”

Mr. James Lawrence Kernan was a theater owner, showman and

philanthropist. After a visit to the hospital, he purchased the Radnor Park

estate in West Baltimore, and deeded it to be the hospital.

In 1911, after converting the mansion into a working hospital,

the name was changed to The James Lawrence Kernan Hospital and Industrial School

of Maryland for Crippled Children, Inc. It is now part of the University of

Maryland.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Franklin Square Hospital was an outgrowth of former

National Temperance Hospital of Baltimore, located on Calhoun and Fayette

Streets. It was a general hospital for both private and free patients. Being a

Temperance Hospital meant that cases were treated with as little use of

alcoholic stimulants as possible.

Milton Linthicum was the chief surgeon at Franklin

Square for many years.

In 1957,

Franklin Square Hospital purchased a 41-acre site in Baltimore county for a

modern general hospital of approximately 300 beds. By 1964, Franklin Square

Hospital moved to eastern Baltimore County to serve 165,000 people in Dundalk,

Essex and Middle River area.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The original Sydenham Hospital for Communicable

Diseases was constructed near Bay View Asylum and opened in 1909. Almost

immediately, the 35-bed facility was deemed “fatally inadequate” for the needs

of a city of 600,000.

In 1922, architect Edward Hughes Glidden submitted

plans for a nine-building campus near Lake Montebello that could care for up to

140. The campus was built in the Italian Renaissance Revival style and opened

in 1924. It was equipped to treat more contagious diseases, ranging from polio

to whooping cough to typhoid, and was in a location that would allow room for

expansion.

By 1949, the need for care for contagious

diseases had dwindled, but it was still being used to treat tuberculosis

patients. In the 1950’s, the property was renamed and opened as Montebello

State Hospital. Nearly $3 million was spent on renovations and additions.

Staffing shortages plagued the hospital and in the 1960s it closed for good. Many

of the buildings were demolished, although several are still being used by

Morgan State University.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Happy Hills Convalescent Home was founded by

the 22-year old Hortense Miller Eliasberg as a graduate school project for

children who had been hospitalized but needed a healthy place to recuperate. She

enlisted Dr. William Welsh as President.

The first location was a

farm-house on Poplar Hill in North Roland Park. They outgrew the space by 1928

and relocated to Rogers Avenue, where they are now. In the 1950’s, the name was

changed from Happy Hills Convalescent Home to Mt. Washington Pediatric

Hospital.

Ironically, the earliest

children came to Happy Hills because of malnourishment, but now they come

because of obesity.

The Mt. Washington

Pediatric Hospital is the only jointly owned project of Johns Hopkins and the

University of Maryland Medical System.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This is the list of resources that I used to research this lecture.

Thank you for reading!